Let’s say you’re taking charge of your health and want to walk every day in your neighborhood. Or, you’d like to teach your kids the self-reliance skill of biking to school. Well, if sidewalks aren’t there, or you don’t feel comfortable using them, achieving those goals won’t be possible. That’s why the attitudes of the public agencies who plan streets and sidewalks really matter. The health of a community is literally in their hands. By baking in the opportunity for exercise on sidewalks, bike lanes, and trails, they also build a healthy population.

Only recently has transportation been directly linked to health. Research now proves that if you walk, bike or otherwise use your muscles on a regular basis, you can avoid or lessen a host of metabolic and other diseases, including obesity, heart disease, depression, and type-2 diabetes. It’s easiest to be physically active if the opportunity is right outside your door.

A few success stories from the Durable Human post, “How Walking Can Save America“:

- 3,000 borderline diabetics who walked 30 minutes 5 days a week over a 6-month period reduced their diabetes risk by 50%.

- After the city of Charlotte, North Carolina opened a light rail line in 2007, drivers who switched to the train (and therefore walked more) lost an average of 6 pounds and reduced their long-range chances of becoming obese by 81%.

- Older Americans who walked 45 minutes 3 days each week for a year had a 2% increase in brain volume while the brains of those who didn’t exercise shrank by 1.5%.

For about the last hundred years, street planning has focused on how to make driving a vehicle safe and unimpeded. But lately, transportation planners have reawakened to the needs of other road users. “Multimodal” is the parlance for this kind of comprehensive planning: making it safe and convenient for people to have a variety of options to get from here to there.

Until now, however, due to a lack of sanctioned guidelines, many agencies have been reluctant to go beyond car-centric planning. A new survey of state departments of transportation finds that, when planning road projects, most agencies rely on “engineering judgment” when it comes to including other modes, and 75% of respondents admit they have no procedures for multimodal risk analysis.

Thankfully, though, some new tools are here to help. Introduced at the highly respected Transportation Research Board, an arm of the National Academies of Sciences, the resources are expected to have wide-ranging influence on creating or improving the “built environment,” i.e., streets, sidewalks, and associated accoutrements, such as traffic signals.

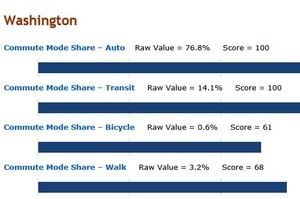

States and metropolitan areas can now easily incorporate health measures and goals into transportation planning using the U.S. Department of Transportation’s aptly-named Transportation and Health Tool. Agencies can use the web-based platform to custom-design strategies for improving their own community’s health through transportation plans and policies.

States and metropolitan areas can now easily incorporate health measures and goals into transportation planning using the U.S. Department of Transportation’s aptly-named Transportation and Health Tool. Agencies can use the web-based platform to custom-design strategies for improving their own community’s health through transportation plans and policies.

Another new arrival is the Federal Highway Administration’s Guidebook for Developing Pedestrian and Bike Performance Measures. This is also a free, interactive tool agencies can use to “take a look at what are their overarching community goals and how they can find measures that really align with those goals to help evaluate and track and implement pedestrian and bicycle systems,” explains Karla Kingsley, co-author of the Guidebook.

Included is a Performance Measures Toolbox that presents how 30 different considerations (such as Job Creation, Land Value, and Connectivity) tie into each travel mode. For example, the Toolbox might make it clear in a road widening plan that including bike lanes will provide a missing link in the regional bicycling network.

At this point you may be thinking: That’s all well and good, but the vast majority of road users are drivers, so shouldn’t they count for more in the road design?

“I don’t think the tool is meant to replace vehicular Level of Service (LOS),” says Kingsley. “In fact, one of the measures we have in the guide is LOS, but it’s applied to all modes, so ‘multimodal LOS’. So, we can look at LOS for vehicles, but also look at it for bicyclists, pedestrians, and people riding transit and you can really see how the transportation network is serving all these different modes.”

Kingsley explains how the Guidebook ties into health in this 2-minute interview:

Also see Guidelines for Designing Low and Intermediate Speed Roadways That Serve All Users. The guidelines pertain to the majority of streets in suburbia and almost all of them in cities: those with speed limits of 45 miles per hour or less.

While all this new transpo thinking shakes out, the easiest way for you to get a running start on good health and overall durability is to live in a place where sidewalks, bike lanes, and transit stops are already there.

If you’d like practical tips and tricks for doing your own personal land use planning, read How To Be a Durable Human: Revive and Thrive in the Digital Age Through the Power of Self-Design.

About the author: Jenifer Joy Madden is a health journalist, digital media adjunct professor, and award winning active-community advocate. When she realized she couldn’t walk safely with her young son from their home to a nearby park, she became a self-taught land use planner and won public support for her vision of Virginia’s first “Leave No Child Inside Corridor,” (also known as the NoVi Trail Network): a system of sidewalks and trails connecting one national park, two regional parks, ten local parks, three schools, one town, and Tysons – a revitalized edge city of Washington, D.C. Read more about the health benefits of active design and why Fairfax County, Virginia, serves as a national model for supporting the durability of its young people through its free student bus ride program in Jenifer’s book, How To Be a Durable Human: Revive and Thrive in the Digital Age Through the Power of Self-Design.