Many are puzzling over how digital technology can be designed to work more for us than against us. But countless such tools already exist to do that—it’s just a matter of how we use them. This is a personal example of how individuals orchestrated our public-serving governmental entities and digital creations to improve a community’s quality of life.

On a beautiful day in 1999, a few years after we moved to our newly-built suburban neighborhood near Washington, D.C., I got the urge to walk with my six-year-old son to a nearby park.

This was no ordinary destination, but the serene and meticulously cared-for Meadowlark Botanical Gardens, the only such facility in all of northern Virginia.

Though barely a mile long, the walk itself was tough. We fought through tall grass along winding Beulah Road—surely trespassing on other people’s yards. As we trudged ahead, we noticed a trampled area, replete with the fresh detritus of a car accident.

Scattered before us were a rear-view mirror, tape unspooled from a cracked cassette, and lengths of clear medical tubing. A few years later I would meet the father of the college student airlifted by medevac from the scene just the night before, after her car struck a dump truck head-on as it rounded the curve. Her life was never the same.

A few months later, I noticed an announcement taped to a door at Wolftrap, my son’s public elementary school. Catherine Hudgins, the newly-elected Supervisor of Hunter Mill—our district of Fairfax County—was holding a get-to-know-the-community listening session.

Though I’d never been involved in a political or civic process, it struck me as an opportunity.

Seeing The Bigger Picture

After asking my neighbor Gretchen McLeish for help pulling together some county data about the local traffic and population, I looked at a map of our area of Vienna.

It was then I had an epiphany: not only did we live near one, but also a whole host of outstanding parks—all within walking distance.

The green on the map formed almost a ring around us. The public parkland included one national, two regional, and at least eight county parks. How great would it be if anyone living in our area could safely walk and bike to all of them?

I saw how almost every park could be reached via existing streets. Using SoHo (pronounced Soe Hoe)—the part of New York south of Houston Street—as my model, I sketched out a star-like route to connect them and dubbed it the NoVi (pronounced Noe Vee) Trail Network—short for Northern Vienna.

The Supervisor listened intently as I showed my charts and map: more cars, more people were crowding into the neighborhood—yet we couldn’t safely reach our wealth of nearby public facilities without having to drive.

When I asked how we could acquire more sidewalks, she responded, “If you can get other people interested, come back and see me.”

At that moment, I became a community organizer.

Beginning the NoVi Trail Network Movement

We would need a place for interested people to get together. Meadowlark had meeting rooms, so why not start there? As he has for all our meetings since then, park manager Keith Tomlinson did not hesitate to say Yes. In fact, we could use the attractive atrium rentable for wedding receptions—at no charge.

About 30 people showed up on that cold November night. Among them, residents living next to the park who were spoiling for a fight. In no way would they accept a trail around Meadowlark’s periphery. A pre-existing agreement had ensured that no strangers would ever traverse their back yards. “Of course a trail won’t go there,” I assured them, because the route I envisioned did not need to.

Relieved at averting a confrontation, I explained the vision for the trail network, then set out two clipboards: one for signatures of those supporting the trail concept and another for anyone willing to volunteer to help.

When several people stepped up to sign both, I knew this dream could become a reality.

I would need some education. My homeowners association readily agreed to fund my registration for the Governor’s Conference on Greenways and Blueways. There, I learned the basic terms and practices of land use and transportation planning, as well as about state and federal grants that paid for sidewalk and trail projects. Bicycling advocate Bruce Wright worked for Supervisor Hudgins at that time and enlightened me to the pre-existing Countywide Trails Plan, which already envisioned some of the sidewalks and trails along the proposed NoVi Trail Network route.

So, when I went to inquire at Fairfax County about how to get sidewalks built, and was told “We have no money,” I knew that was not the end of the line.

Ultimately, it would take a hodge-podge of grants from various government agencies to complete the network. These were supplemented by “in-kind” donations—credits in money for the hours and hours we amateur planners spent working on the project.

By the time I had rounded up support and returned to the Supervisor, she was no longer a rank beginner. Many people and causes had already caught her ear.

But—just hours before the application closed for a small federal multi-modal transportation grant and at the insistence of her trail aide Merrily Pierce—Supervisor Hudgins agreed to put up a few thousand taxpayer dollars as match money to obtain a grant.

The grant would fund a feasibility study. She would go only that far because she wanted proof. Proof, not only that the community supported the plan, but that the project was buildable—from an engineering, utilities relocation, and property ownership perspective.

The Supervisor appointed a local resident living in each of the network’s four segments to serve on the feasibility study advisory committee. Together, they developed a survey for all residents in the designated study area.

Distributed to 1800 local households, the survey showed 85% of respondents either supported or strongly supported the trail plan. Among other findings: 87% of respondents wanted an opportunity to exercise, 80% wanted to “travel in ways other than car”, and 64% wanted their kids to be able to walk or bike to school.

For the study, architect Reed Black—who lived in the neighborhood and was co-Chair with me on the advisory committee—did a tremendous amount of mapping work.

To show where public property existed along the route, Reed took pictures of his son wearing a bright orange shirt standing on the line separating private property from public right-of-way.

Reed’s property maps and the county’s land-use analysis showed there was plenty of publicly-held land along the route and that there were no significant engineering issues.

Getting the Go-Ahead for the NoVi Trail Network

In 2007, the year after the survey results were released, Supervisor Hudgins included the project in Hunter Mill’s requested projects list and Fairfax County voters approved a Transportation Bond Referendum funding the backbone of the trail plan.

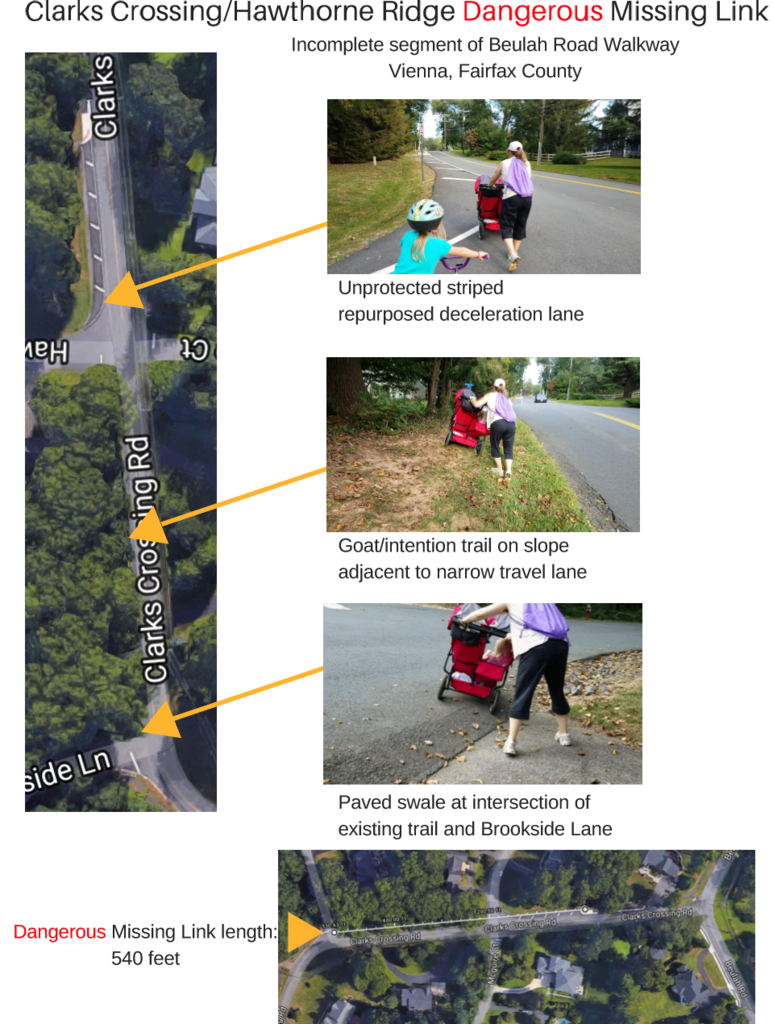

In the next ten years, the sidewalks and trails of all four primary segments of the NoVi Trail Network became a reality—almost.

After years of fruitless negotiations with one final property owner, the county officially closed the project. But when we learned that, trail supporters wouldn’t give up.

First, we alerted the larger community to the danger posed by the missing link through some compelling photos and video—thanks to a brave volunteer walker and her offspring.

We then then contacted the property owner—enlisting the help of local resident and retired U.S. Transportation Department attorney Bern Diederich. After several meetings with trail volunteers, county staff, and the owner’s attorney, the parties brokered an agreement for a sidewalk to be built in the public right-of-way next to his property.

In January 2022, the Fairfax County Department of Transportation, in cooperation with planning by the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), eliminated the “dangerous missing link” by constructing an ADA-compliant trail in its place.

More Avenues to Success

As the county designed the first sidewalk segments, another aspect of the network was about to take root. So many government agencies would need be involved, I was told it simply couldn’t be done. But Virginia’s U.S. Representative James Moran was up to the challenge.

As the only national park for the performing arts, Wolf Trap is beloved by visitors near and far. When my next door neighbor Susan Sullivan and I showed the congressman photos of a wayward pedestrian attempting to cross the bridge over the Dulles Toll Road to the park, he agreed that vital safety improvements were needed.

Over a period of years, and with the cooperation especially of VDOT and the Eastern Federal Lands Highway Division of the Federal Highway Administration, the congressman obtained enough federal funding to construct a free-standing pedestrian bridge parallel to the existing car bridge.

In the middle of one night in 2012, trail volunteer stalwart Dan Benson, my husband, my older son, and I watched—wineglasses in hands—as cranes assembled the three-section structure.

Meanwhile, around that same time, a truck preparing the highway for the arrival of Metro accidentally struck and severely damaged the underside of another bridge over the Toll Road—this one on Beulah Road adjacent to Meadowlark Gardens.

After I called the Supervisor’s office with the suggestion, it didn’t take much convincing for VDOT to add a sidewalk and bike shoulder when the bridge was repaired.

Yet another concurrent effort created more critical connections within the NoVi Trail Network.

It just so happens that Meadowlark Botanical Gardens and the W&OD Trail are both managed by the Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority, now known as NOVA Parks.

A legal way to add a trail connection between the two parks—called an “easement”—existed, but two property owners living on and near the easement were actively blocking the possibility. But after years of nudging by NoVi trail supporters, NOVA Parks went to court and an agreement was hammered out to create the beautiful paved connection that now exists, including a picturesque boardwalk over the wetlands.

Now, not only have all the sidewalks and trails planned for the NoVi Trail Network been built or are in design, but both bridge crossings over the Dulles Toll Road are much safer for walkers and cyclists.

As Supervisor Hudgins so aptly wrote in a letter to property owners living along the trail, “It is important to keep in mind that none of this progress would have been possible without the participation of so many of you.” Quiet support from hundreds and hundreds of other community members, dedication by numerous elected officials and their staffs, and the hard work of dozens of public servants (and their computers) from multiple agencies were also essential to the process.

Ripples from the NoVi Trail Network Effort

The trail network planning effort has had broader repercussions and indeed came full circle.

Culture Change at Wolftrap Elementary

Before the existence of the NoVi Trail Network, students at Wolftrap Elementary arrived almost exclusively by car or bus. When the existing bits of sidewalks were connected to make a continuous route, it became easier for more children to walk and bike to school.

The transformation began in earnest in 2010 when Jeff Anderson, a cycling-loving dad began to lead his own and other students on “bike trains” to school. Jeff’s efforts coincided with a nascent Bike to School Day movement.

Now, almost every day at Wolftrap—where I had seen Supervisor Hudgins’ community meeting notice a decade before —bike racks are full. Parents share coffee donated by Caffe Vienna after weekly “Walking Wednesdays.” The school culture has been permanently changed from car- and bus-dependent to giving many children the health-enhancing option of walking and biking.

Creating Access to Tysons Metrorail

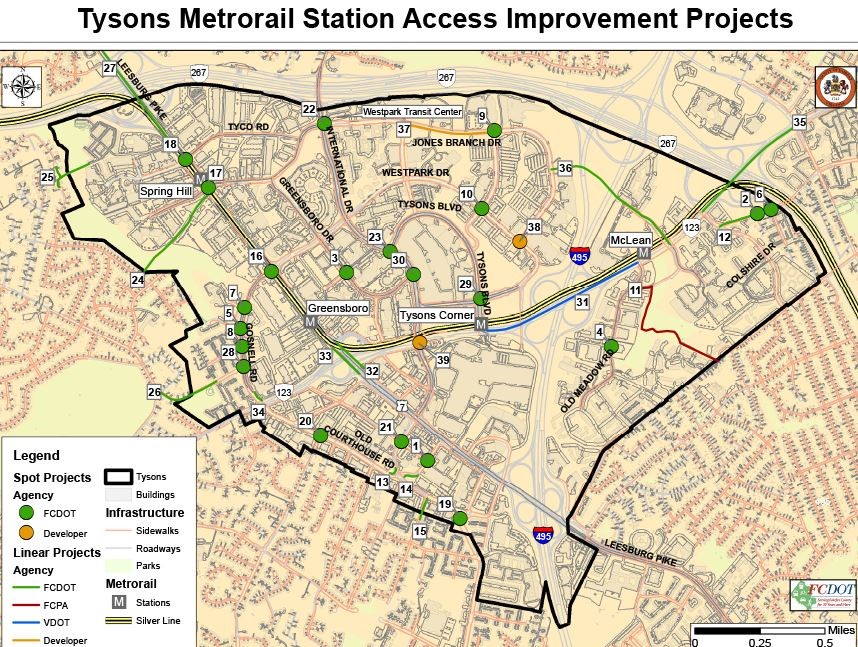

In 2000, the idea that Tysons Corner would become Fairfax County’s new downtown lived only in the county’s comprehensive plan. The Tysons Land Use Task Force would not begin its work until 2004. But from the first days of the vision for the NoVi Trail Network, it was clear that new trails would make it safer and easier for residents to bicycle to Tysons, downtown Vienna, and beyond.

When Metrorail’s arrival in Tysons became a reality, it dawned on me that scant attention was being paid to how those in the surrounding areas could get to the Metro stations, which were being planned urban-style—with no car parking lots.

I asked Merrily Pierce—the same Hudgins transportation aide who helped get NoVi through the approval process—how we could change that.

Based on a plan for non-motorized access to Metro stations in nearby Reston, she and the Supervisor invited the other two county districts Bordering Tysons (Dranesville and Providence) and the town of Vienna to create the Tysons Metrorail Station Access Management Study (TMSAMS).

After many meetings of the TMSAMS Task Force—including citizens such as myself, business representatives, and county staff members—Fairfax County transportation planner Kris Morley-Nikfar combined maps of the existing sidewalks, trails, bike routes, local, and regional bus routes into one map.

The multi-modal map was then posted online and the community voted for their favorite routes to walk, bike and take the bus to Tysons Metro stations. Those priorities were then were funded in the Tysons implementation plan.

A Multi-modally Minded Community

Among the routes identified in TMSAMS was a bus loop through northern Vienna streets to the Springhill Metro station. But when it came time for public hearings, a neighborhood near—but not on—the NoVi Trail Network alignment fiercely opposed the bus line. Meanwhile, neighborhoods that had been exposed to messages about the benefits of a multi-modal transportation through the NoVi planning process were in support.

During the hearings, these neighbors spoke up for the bus line against their nearby neighbors’ vehement opposition. Ultimately, the Board of Supervisors—led by Supervisor Hudgins—approved Route 432, which still runs today during morning and evening rush hours.

The origin story of the NoVi Trail Network, instructions for how to start a Walk and Bike to School effort, and the ways free and unstructured physical activity such as walking and bicycling benefit durability, health, and wellness are all found in the book How To be a Durable Human: Revive and Thrive in the Digital Age Through the Power of Self-Design, written by the mom who took her son on that fateful walk to Meadowlark. That’s me—Jenifer Joy Madden.