Can simple tasks like cooking dinner and washing the dog help break a crippling compulsion to overuse screen-based media? To find out, I traveled to America’s first Internet addiction treatment center, in the outskirts of Seattle. I was told beforehand to “please keep your phone on silent and out of sight.” Here’s what happened:

At the end of a long driveway, pine branches thick with moss hang over the roof of a split-level house. Hilarie Cash is there to greet me. Voices emanate from the garage, where a trainer works out with “the guys.” That’s Hilarie’s term because her clients are almost always men of a certain age. Ordinarily, they might be in college.

They smile politely as we interrupt. While Hilarie makes introductions, the house dog pads in and I lean down to give her a skritch. “I have a dog!” a guy eagerly exclaims. “Want to see pictures?” “Maybe later,” Hilarie answers for me.

Hilarie Cash, PhD, is a licensed mental health counselor who began treating various forms of tech addiction in the mid-1990s. Over the years, she made good progress with most clients in an office setting, but video game addiction was more recalcitrant. As she recalls, “I was frustrated because there was no place appropriate to send our gamers.” (Watch my entire interview with Hilarie below)

Clinical social worker Cosette Rae saw the same need in her practice. So in 2009, the pair created ReStart after Rae’s builder husband converted their home to serve as a campus for the first phase of the adult program.

With night falling, Hilarie and I head back outside. A couple of tiny cottages dot the back yard. One is snug enough for just a person or two. The other, deeper in the woods, is filled with an arc of comfy chairs. In the center, an hour glass sits on a coffee table, atop a worn oriental rug.

Closer to the house, a narrow creek trickles beside the remnants of a vegetable garden as mammoth chess pieces stand sentinel.

“If you’re just away from all aspects of the Internet and screens for long enough,” Hilarie muses, “your body will detox and you’ll have a new perspective and experience yourself and your world in a different way.”

About 250 adults have been treated so far at ReStart. A program for kids ages 13 to 18 opened nearby early in 2017. It was in great demand, according to Hilarie. “Even if somebody comes here and they’re kind of resistant and in denial about needing it, that often changes in the course of being here for seven or eight or nine weeks.”

Back inside, we pass through the kitchen and step down into a living room with large windows and a stone hearth. A client sits by himself on the couch with a pen and notebook.

“What? You’re not working out?” Hilarie chides him. “I’m journaling. It’s loud in there,” he replies, gesturing toward the garage.

He is one of the six clients who live here. They bunk in spartan bedrooms. Hilarie opens the door to each and—other than a wayward sock—all are neat and tidy.

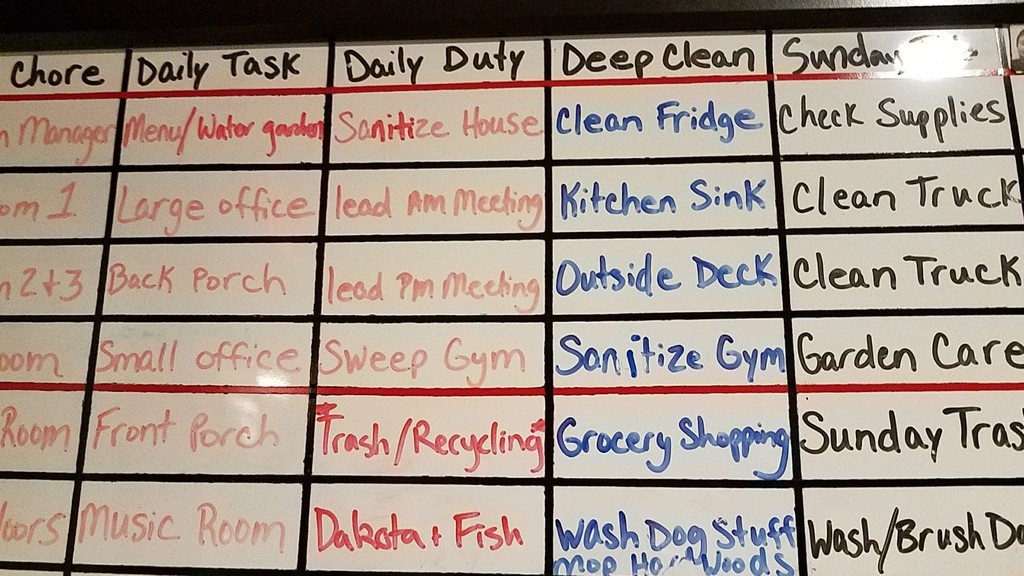

On a wall in the hallway, a chore board brims with daily tasks, duties, and “deep cleans.” Sanitize Gym, Grocery Shopping, Trash/Recycling, Wash/Brush Dog. Every day every guy has responsibilities.

“A lot of them have been allowed, really, by their parents to really not function at a high level,” Hilarie explains later. “And so they often don’t know how to cook, they don’t know how to shop for food, they don’t know how to do their laundry sometimes. Our goal is that they’ll be really ready to function like independent young adults by the time they move out.”

Back in the kitchen, photos of a Siberian Huskie pup are making the rounds. “His name is Maximus!” the proud owner proclaims, tending a passel of sizzling steak segments, adding wistfully: “I miss him.”

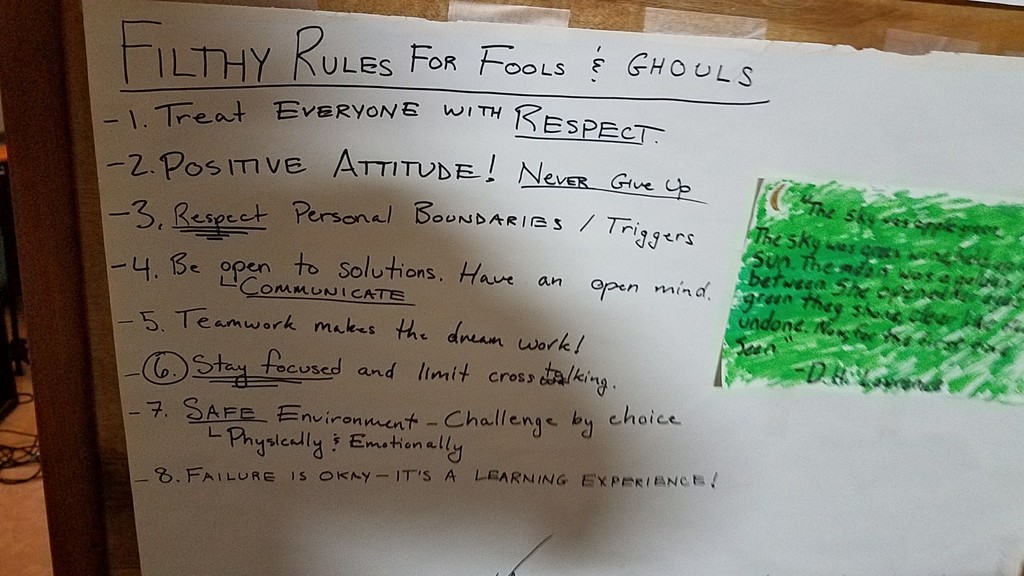

Beside the dinner table, a white board is scrawled with eight handwritten rules. Number six is circled: “Stay focused and limit cross talking.”

In the staff-only area upstairs, Hilarie tells me, “The skills that they lack are not only life skills, but skills of emotional regulation, skills of communication, social skills. When you don’t have skill in that, it’s extremely anxiety-provoking. What their habit is, is to escape from those difficult emotions through the distraction of their online activities.

It’s complicated learning how to read peoples’ faces, to pick up on non-verbal body language, and you need practice at it. These guys haven’t had very much practice because online communication is very different from offline communication, face-to-face. They need to practice not only the skills but how to handle the emotion that comes up.”

From what Hilarie’s observed, many clients have what she calls “Mr. Nice Guy Syndrome.” “They are so often afraid of conflict. And, so to avoid conflict, they will acquiesce, they will withdraw, they will say ‘yes’ but not do it, and it leads to resentment, which fuels addiction. Once that neuro-biological process has happened, they lose control. Once they’ve lost control, they’re going to engage in it, despite all the negative consequences.”

Many parents have high hopes when their gamers go off to college, thinking campus life is still what it used to be. “What happens instead,” says Hilarie, “is that some of them find themselves without the parental structure that was there before, keeping a lid on things. They’re faced with increased stressors of having to create a social life, and having rather poor social skills, and lack of confidence socially, and increased academic pressure. And the guys who come here are the guys who just retreat from those challenges, and hide away and just really jump off the cliff.”

Hilarie says it’s a coincidence that the first Internet addiction treatment facility in the U.S. is within a dozen miles of Microsoft headquarters.

Back downstairs, I meet Jeff (not his real name). Bright-eyed behind dark-rimmed glasses, he sits cross-legged on the couch vacated by the journal writer. Now I’m the one with the pen and notebook.

At 22, Jeff says he’s been with ReStart “forever”—which amounts to a year and a month.

Jeff tried “at least twice” to make it in college. “In high school, I played video games, but I had a girlfriend and was on the swim team. It was the opposite in college.”

There, nothing seemed to jibe. “No one talked to me. I felt extremely alone.”

Unless, that is, he was playing League of Legends. “We played five on five. I always moved up and people valued me.”

League of Legends is a 3D strategy video game known as a Multiplayer Online Battle Arena. When Jeff arrived at ReStart in 2016, 100 million people a month were on the game.

After washing out of school yet again, Jeff returned home. He swore to his parents he wasn’t gaming, but continued behind their backs. At wits’ end, they finally told him he had to leave home. From there, he says, “I kind of had a breakdown. In the E.R., a nurse took pity on me and got me a cot.”

After that, he lived almost three months in a homeless shelter. Somehow, he also held down a part-time job. That left ample time for what he calls a “PC gaming bar” : “On weekdays, the hours were 12 pm. to 2 a.m. On weekends, it was 12 p.m. to 4 a.m. I was there every day from open ’til close.”

One day, Jeff’s parents called him on the phone at work. (He’d lost access to a cellphone months before). He remembers the conversation: “They asked, ‘Are you happy? Do you still want to play games?’ They said I could come home if I got on the ReStart waitlist.”

As is typical at ReStart, Jeff lived at the house for about eight weeks. After that, he continued treatment but transitioned to a ReStart-leased apartment.

Now he’s in the final pre-independence phase. He has another part time job and rents a place with four other ReStart graduates: “Everybody signs an agreement not to play video games. If they do, they’re kicked out.”

During his months at ReStart, Jeff says, he “gained the willingness to change.” He admits needing help on social skills. “When I’d talk to people, I was anxious and had a knot in my stomach. I’d put on a false persona. I was insecure and not self-confident.”

But at ReStart, he says, “I learned how to live. They taught me the building blocks to have my own life.”

Jeff thinks he’ll be ready to move on in a couple of weeks. He’s been home for a visit and is getting along with his parents. “It’s nice to hear that they love me. Before they didn’t trust me because I’d always lie to them.”

On the outside, Jeff wants to be “somewhat of a role model.” As he told me, “Part of being an addict is you always have this thought in the back of your mind which pops up. It could be boredom, or your room’s dirty.” Now he feels ready to talk about it: “I’m doing fairly well, I’m stable and never relapsed.”

He’ll start with one class at a Seattle-area community college and again work part-time, but this time approaching it differently: “I like to be early to a job now.”

As I thank Jeff for his story, we stand up. I notice he’s very tall, but he stands with his feet apart so we’re closer to the same eye level.

By that time, the kitchen is clean and most of the guys are getting ready to leave for a weekly session of mindful meditation.

The sitting room holds several kinds of instruments and a working phone booth. The words “Everyday holds the promise of a Miracle” is written on the wall.

Before heading out, I ask Hilarie about the future. She’s worried—especially about the potential of virtual reality. “The more immersive an experience, the more intense it will be, intensely pleasurable. If you’re a gamer and you can be completely immersed in your cyber reality, digital reality, that immersion is going to release more of those neurochemicals than something less immersive.”

We return to the topic of what works to reverse an Internet addiction. Nature, she tells me, and plenty of physical activity. It’s about balance and non-threatening human contact, as they have at ReStart: “Here is an intimate, safe social setting. Plenty of sleep. Healthy food. Building skills that help you feel confident and competent. All of these things are antidotes. And so that’s what we’re trying to provide here, as well as psychotherapy to address any deep issues that need to be addressed.”

~~~

Outside, the moon peeks from between the clouds. Starting the car, I reach for my phone, then pull my hand away. I try instead to remember the way back to where I am staying, and manage to get there, no problem.

Read more about how to know if you or a loved one is addicted.

Get a free checklist for planning your family’s time wisely:

Watch my half-hour interview with Hilarie Cash:

Read Hilarie’s book, Video Games & Yours Kids: How Parents Stay in Control, with chapters on all different age levels and includes “The Formal Intervention Option.”

About the author:

Jenifer Joy Madden is a parent educator, health journalist, and digital media adjunct professor who founded DurableHuman.com and wrote How To Be a Durable Human: Revive and Thrive in the Digital Age Through the Power of Self-Design.

All photos by the author